Reflection

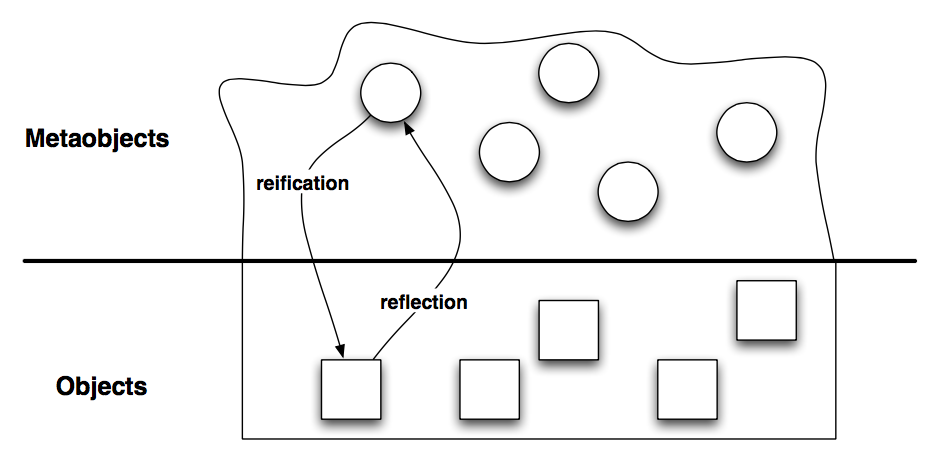

Smalltalk is a reflective programming language. In a nutshell, this means that programs are able to “reflect” on their own execution and structure. More technically, this means that the metaobjects of the runtime system can be reified as ordinary objects, which can be queried and inspected. The metaobjects in Smalltalk are classes, metaclasses, method dictionaries, compiled methods, the run-time stack, and so on. This form of reflection is also called introspection (反省), and is supported by many modern programming languages.

Reification and reflection.

Conversely, it is possible in Smalltalk to modify reified metaobjects and reflect these changes back to the runtime system. This is also called intercession, and is supported mainly by dynamic programming languages, and only to a very limited degree by static languages.

A program that manipulates other programs (or even itself) is a metaprogram. For a programming language to be reflective, it should support both introspection and intercession. Introspection is the ability to examine the data structures that define the language, such as objects, classes, methods and the execution stack. Intercession is the ability to modify these structures, in other words to change the language semantics and the behavior of a program from within the program itself. Structural reflection is about examining and modifying the structures of the run-time system, and behavioural reflection is about modifying the interpretation of these structures.

In this chapter we will focus mainly on structural reflection. We will explore many practical examples illustrating how Smalltalk supports introspection and metaprogramming.

Introspection

Using the inspector, you can look at an object, change the values of its instance variables, and even send messages to it.

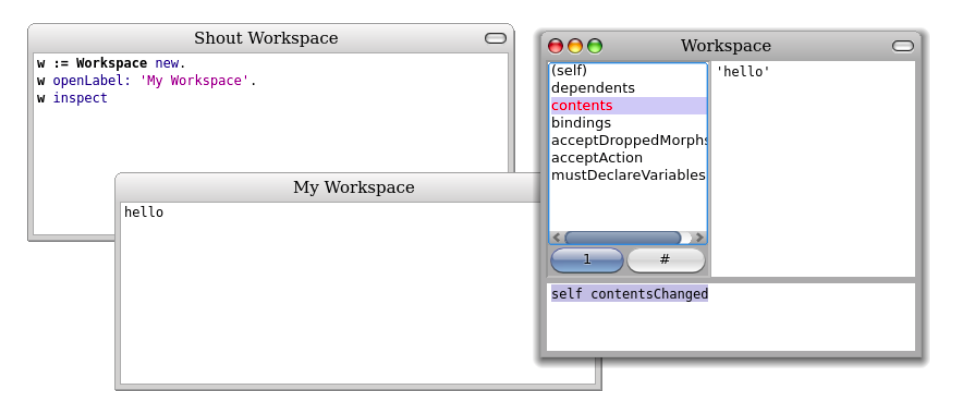

Evaluate the following code in a workspace:

w := Workspace new.

w openLabel: 'My Workspace'.

w inspect

This will open a second workspace and an inspector. The inspector shows the internal state of this new workspace, listing its instance variables in the left part (dependents, contents, bindings...) and the value of the selected instance variable in the right part. The contents instance variable represents whatever the workspace is displaying in its text area, so if you select it, the right part will show an empty string.

Now type 'hello' in place of that empty string, then accept it.

The value of the contents variable will change, but the workspace window will not notice it, so it does not redisplay itself. To trigger the window refresh, evaluate self contentsChanged in the lower part of the inspector

Accessing instance variables

Inspecting a Workspace.

by numeric indices. The inspector uses methods defined by the Object class to access them: instVarAt: index and instVarNamed: aString can be used to get the value of the instance variable at position index or identified by aString, respectively; to assign new values to these instance variables, it uses instVarAt:put: and instVarNamed:put:.

For instance, you can change the value of the w binding of the first workspace by evaluating:

w instVarNamed: 'contents' put: 'howdy’; contentsChanged

Caveat: Although these methods are useful for building development tools, using them to develop conventional applications is a bad idea: these reflective methods break the encapsulation boundary of your objects and can therefore make your code much harder to understand and maintain.

Both instVarAt: and instVarAt:put: are primitive methods, meaning that they are implemented as primitive operations of the Pharo virtual machine. If you consult the code of these methods, you will see the special pragma syntax <primitive: N> where N is an integer.

Object >>

instVarAt: index

"Primitive. Answer a fixed variable in an object. ..."

<primitive: 73>

"Access beyond fixed variables."

^ self basicAt: index − self class instSize

Typically, the code after the primitive invocation is not executed. It is executed only if the primitive fails. In this specific case, if we try to access a variable that does not exist, then the code following the primitive will be tried. This also allows the debugger to be started on primitive methods. Although it is possible to modify the code of primitive methods, beware that this can be risky business for the stability of your Pharo system.

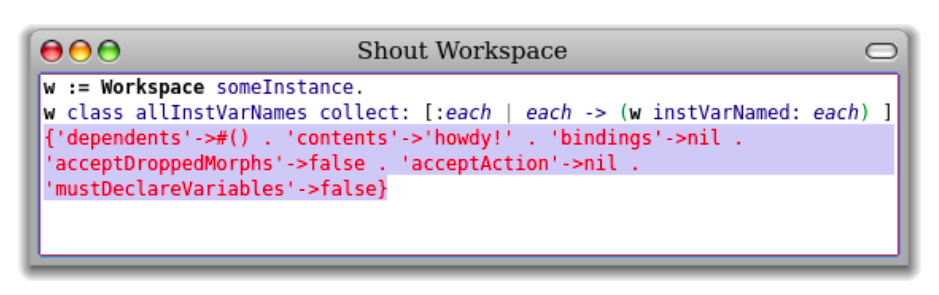

Displaying all instance variables of a Workspace.

shows how to display the values of the instance variables of an arbitrary instance (w) of class Workspace. The method allInstVarNames returns all the names of the instance variables of a given class.

In the same spirit, it is possible to gather instances that have specific properties. For instance, to get all instances of class SketchMorph whose instance variable owner is set to the world morph (i.e., images currently displayed), try this expression:

SketchMorph allInstances select: [:c | (c instVarNamed: 'owner') isWorldMorph]

Iterating over instance variables

Let us consider the message instanceVariableValues, which returns a collection of all values of instance variables defined by this class, excluding the inherited instance variables. For instance:

(1@2) instanceVariableValues ---> an OrderedCollection(1 2)

The method is implemented in Object as follows:

Object >>

instanceVariableValues

"Answer a collection whose elements are the values of those instance variables of the receiver which were added by the receiver's class."

|c|

c := OrderedCollection new.

self class superclass instSize + 1

to: self class instSize

do: [ :i | c add: (self instVarAt: i)].

^ c

This method iterates over the indices of instance variables that the class defines, starting just after the last index used by the superclasses. (The method instSize returns the number of all named instance variables that a class defines.)

Querying classes and interfaces

The development tools in Pharo (code browser, debugger, inspector...) all use the reflective features we have seen so far.

Here are a few other messages that might be useful to build development tools:

isKindOf: aClass returns true if the receiver is instance of aClass or of one of its superclasses. For instance:

1.5 class ---> Float

1.5 isKindOf: Number ---> true

1.5 isKindOf: Integer ---> false

respondsTo: aSymbol returns true if the receiver has a method whose selector is aSymbol. For instance:

1.5 respondsTo: #floor ---> true "since Number implements floor"

1.5 floor ---> 1

Exception respondsTo: #, ---> true "exception classes can be grouped"

Caveat: Although these features are especially useful for defining development tools, they are normally not appropriate for typical applications. Asking an object for its class, or querying it to discover which messages it understands, are typical signs of design problems, since they violate the principle of encapsulation. Development tools, however, are not normal applications, since their domain is that of software itself. As such these tools have a right to dig deep into the internal details of code.

Code metrics

Let’s see how we can use Smalltalk’s introspection features to quickly extract some code metrics. Code metrics measure such aspects as the depth of the inheritance hierarchy, the number of direct or indirect subclasses, the number of methods or of instance variables in each class, or the number of locally defined methods or instance variables. Here are a few metrics for the class Morph, which is the superclass of all graphical objects in Pharo, revealing that it is a huge class, and that it is at the root of a huge hierarchy. Maybe it needs some refactoring!

Morph allSuperclasses size. ---> 2 "inheritance depth"

Morph allSelectors size. ---> 1378 "number of methods"

Morph allInstVarNames size. ---> 6 "number of instance variables"

Morph selectors size. ---> 998 "number of new methods"

Morph instVarNames size. ---> 6 "number of new variables"

Morph subclasses size. ---> 45 "direct subclasses"

Morph allSubclasses size. ---> 326 "total subclasses"

Morph linesOfCode. ---> 5968 "total lines of code!"

One of the most interesting metrics in the domain of object-oriented languages is the number of methods that extend methods inherited from the superclass. This informs us about the relation between the class and its superclasses. In the next sections we will see how to exploit our knowledge of the runtime structure to answer such questions.

Browsing code

In Smalltalk, everything is an object. In particular, classes are objects that provide useful features for navigating through their instances. Most of the messages we will look at now are implemented in Behavior, so they are under- stood by all classes.

As we saw previously, you can obtain an instance of a given class by sending it the message #someInstance.

Point someInstance ---> 0@0

You can also gather all the instances with #allInstances, or the number of alive instances in memory with #instanceCount.

ByteString allInstances ---> #('collection' 'position' ...)

ByteString instanceCount ---> 104565

String allSubInstances size ---> 101675

These features can be very useful when debugging an application, because you can ask a class to enumerate those of its methods exhibiting specific properties.

- whichSelectorsAccess: returns the list of all selectors of methods that read or write the instance variable named by the argument

- whichSelectorsStoreInto: returns the selectors of methods that modify the value of an instance variable

- whichSelectorsReferTo: returns the selectors of methods that send a given message

- crossReferenceassociateseachmessagewiththesetofmethodsthatsend it.

Point whichSelectorsAccess: 'x' ---> an IdentitySet(#'\' #= #scaleBy: ...)

Point whichSelectorsStoreInto: 'x' ---> an IdentitySet(#setX:setY: ...)

Point whichSelectorsReferTo: #+ ---> an IdentitySet(#rotateBy:about: ...)

Point crossReference ---> an Array(

an Array('*' an IdentitySet(#rotateBy:about: ...))

an Array('+' an IdentitySet(#rotateBy:about: ...)) ...)

The following messages take inheritance into account:

- whichClassIncludesSelector: returns the superclass that implements the given message

- unreferencedInstanceVariables returns the list of instance variables that are neither used in the receiver class nor any of its subclasses

Rectangle whichClassIncludesSelector: #inspect ---> Object Rectangle unreferencedInstanceVariables ---> #()

SystemNavigation is a facade that supports various useful methods for query- ing and browsing the source code of the system. SystemNavigation default re- turns an instance you can use to navigate the system. For example:

SystemNavigation default allClassesImplementing: #yourself ---> {Object}

The following messages should also be self-explanatory:

SystemNavigation default allSentMessages size ---> 24930

SystemNavigation default allUnsentMessages size ---> 6431

SystemNavigation default allUnimplementedCalls size ---> 270

Note that messages implemented but not sent are not necessarily useless, since they may be sent implicitly (e.g., using perform:). Messages sent but not implemented, however, are more problematic, because the methods sending these messages will fail at runtime. They may be a sign of unfinished implementation, obsolete APIs, or missing libraries.

SystemNavigation default allCallsOn: #Point returns all messages sent explicitly to Point as a receiver.

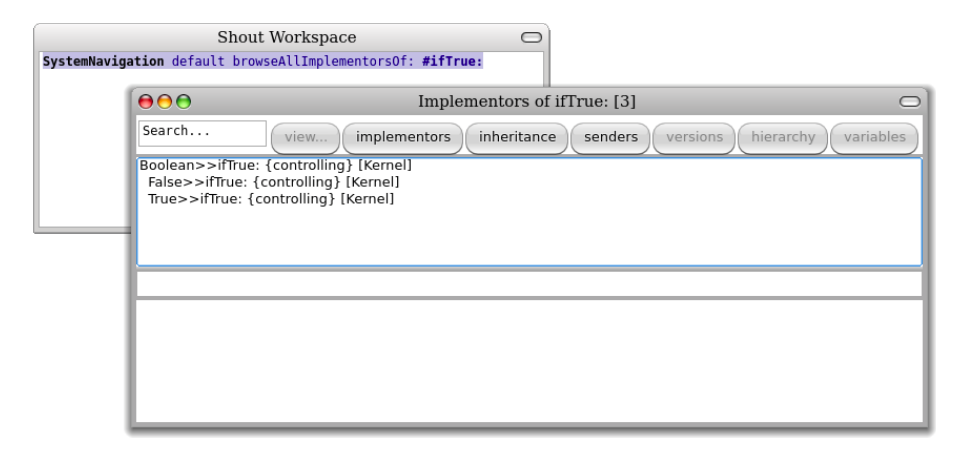

All these features are integrated in the programming environment of Pharo, in particular in the code browsers. As you are surely already aware, there are convenient keyboard shortcuts for browsing all implementors (CMD–m) and senders (CMD–n) of a given message. What is perhaps not so well known is that there are many such pre-packaged queries implemented as methods of the SystemNavigation class in the browsing protocol. For example, you can programmatically browse all implementors of the message ifTrue: by evaluating:

SystemNavigation default browseAllImplementorsOf: #ifTrue:

Browse all implementations of #ifTrue:.

Particularly useful are the methods browseAllSelect: and browseMethodsWith- SourceString:. Here are two different ways to browse all methods in the system that perform super sends (the first way is rather brute force; the second way is better and eliminates some false positives):

SystemNavigation default browseMethodsWithSourceString: 'super'. SystemNavigation default browseAllSelect: [:method | method sendsToSuper ].

Classes, method dictionaries and methods

Since classes are objects, we can inspect or explore them just like any other object.

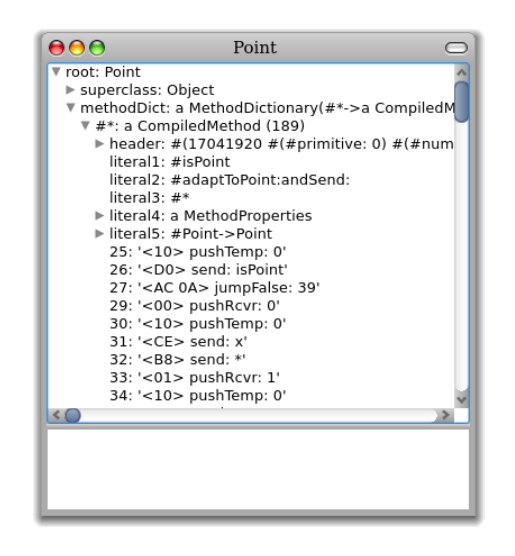

Evaluate Point explore.

the explorer shows the structure of class Point. You can see that the class stores its methods in a dictionary, indexing them by their selector. The selector #* points to the decompiled bytecode of Point >> *.

Explorer class Point and the bytecode of its #* method.

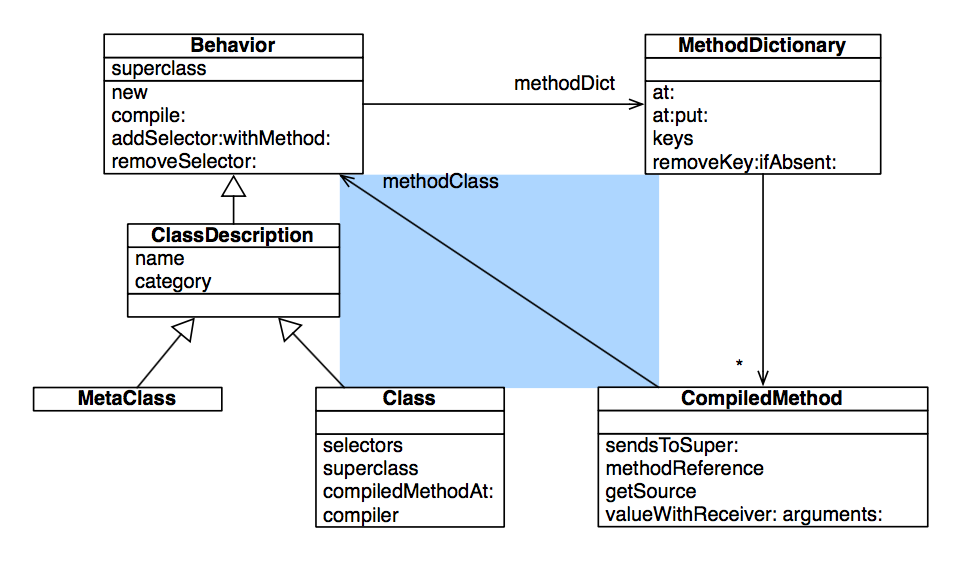

Classes, method dictionaries and compiled methods

Browsing environments

Although SystemNavigation offers some useful ways to programmatically query and browse system code, there is a better way. The Refactoring Browser, which is integrated into Pharo, provides both interactive and programmatic ways to pose complex queries.

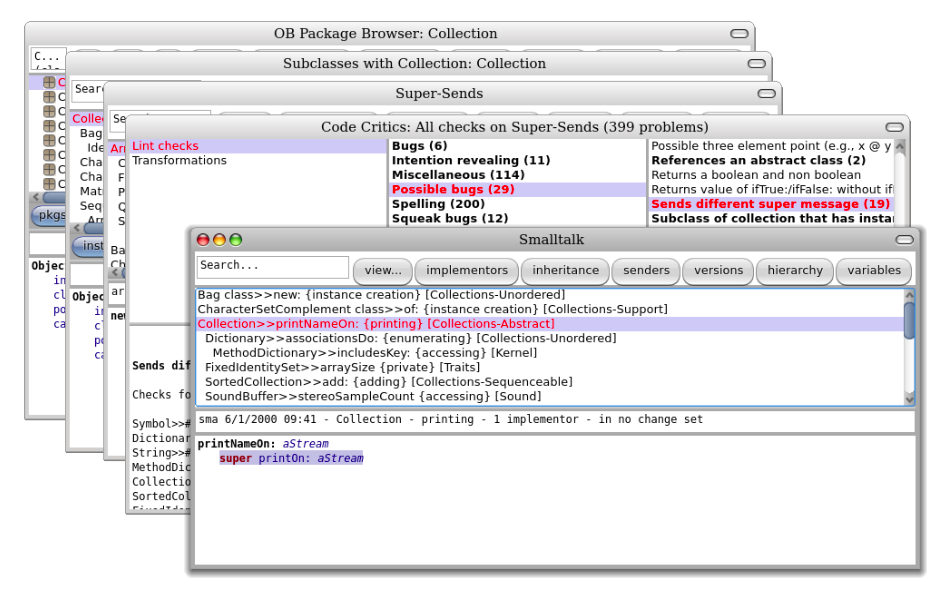

Suppose we are interested to discover which methods in the Collection hier- archy send a message to super which is different from the method’s selector. This is normally considered to be a bad code smell, since such a super-send should normally be replaced by a self-send. (Think about it — you only need super to extend a method you are overriding; all other inherited methods can be accessed by sending to self!)

The refactoring browser provides us with an elegant way to restrict our query to just the classes and methods we are interested in.

Open a browser on the class Collection. action-click on the class name and select refactoring scope>subclasses with. This will open a new Browser Environment on just the Collection hierarchy. Within this re- stricted scope select refactoringscope>super-sends to open a new environ- ment with all methods that perform super-sends within the Collectuon hierar- chy. Now click on any method and select refactor>code critics . Navigate to Lint checks>Possible bugs>Sends different super message. and action-click to select browse.

Finding methods that send a different super message.

Accessing the run-time context

We have seen how Smalltalk’s reflective capabilities let us query and explore objects, classes and methods. But what about the run-time environment?

Method contexts

In fact, the run-time context of an executing method is in the virtual machine — it is not in the image at all! On the other hand, the debugger obviously has access to this information, and we can happily explore the run-time context, just like any other object. How is this possible?

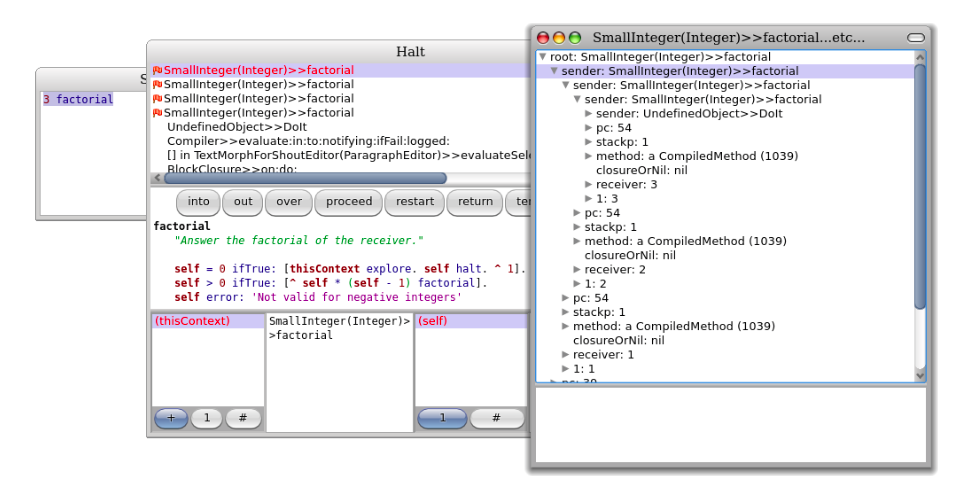

Actually, there is nothing magical about the debugger. The secret is the pseudo-variable thisContext, which we have encountered only in passing before. Whenever thisContext is referred to in a running method, the entire run-time context of that method is reified and made available to the image as a series of chained MethodContext objects.

We can easily experiment with this mechanism ourselves.

Exploring thisContext.

Intercepting messages not understood

So far we have used the reflective features of Smalltalk mainly to query and explore objects, classes, methods and the run-time stack. Now we will look at how to use our knowledge of the Smalltalk system structure to intercept messages and modify behaviour at run-time.

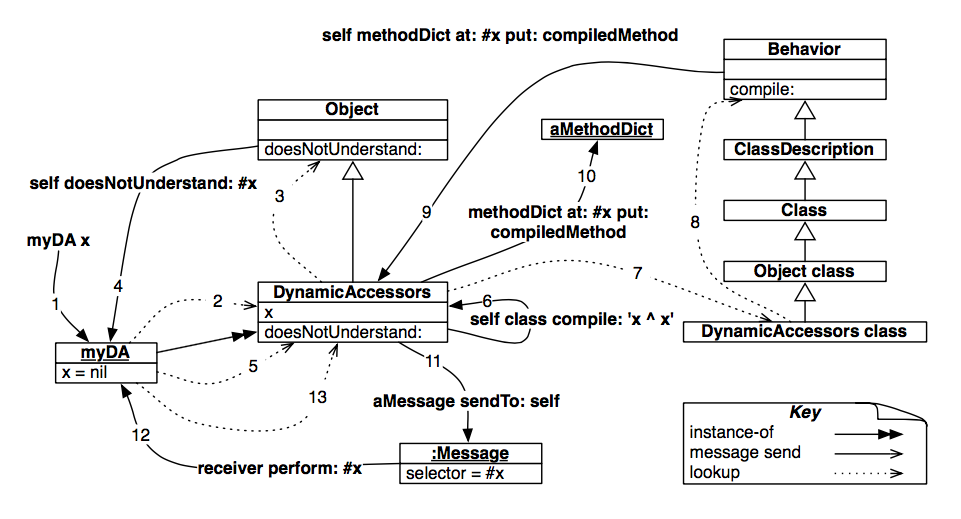

When an object receives a message, it first looks in the method dictionary of its class for a corresponding method to respond to the message. If no such method exists, it will continue looking up the class hierarchy, until it reaches Object. If still no method is found for that message, the object will send itself the message doesNotUnderstand: with the message selector as its argument. The process then starts all over again, until Object»doesNotUnderstand: is found, and the debugger is launched.

But what if doesNotUnderstand: is overridden by one of the subclasses of Object in the lookup path? As it turns out, this is a convenient way of realizing certain kinds of very dynamic behaviour. An object that does not understand a message can, by overriding doesNotUnderstand:, fall back to an alternative strategy for responding to that message.

Two very common applications of this technique are (1) to implement lightweight proxies for objects, and (2) to dynamically compile or load missing code.

Lightweight proxies

In the first case, we introduce a “minimal object” to act as a proxy for an existing object. Since the proxy will implement virtually no methods of its own, any message sent to it will be trapped by doesNotUnderstand:. By implementing this message, the proxy can then take special action before delegating the message to the real subject it is the proxy for.

Generating missing methods

The other most common application of intercepting not understood messages is to dynamically load or generate the missing methods. Consider a very large library of classes with many methods. Instead of loading the entire library, we could load a stub for each class in the library. The stubs know where to find the source code of all their methods. The stubs simply trap all messages not understood, and dynamically load the missing methods on-demand. At some point, this behaviour can be deactivated, and the loaded code can be saved as the minimal necessary subset for the client application.

Dynamically creating accessors.

Objects as method wrappers

We have already seen that compiled methods are ordinary objects in Smalltalk, and they support a number of methods that allow the programmer to query the run-time system. What is perhaps a bit more surprising, is that any object can play the role of a compiled method. All it has to do is respond to the method run:with:in: and a few other important messages.

Define an empty class Demo. Evaluate Demo new answer42 and notice how the usual “Message Not Understood” error is raised.

Now we will install a plain Smalltalk object in the method dictionary of our Demo class.

Using methods wrappers to perform test coverage

Method wrappers are a well-known technique for intercepting messages3. In the original implementation4, a method wrapper is an instance of a subclass of CompiledMethod. When installed, a method wrapper can perform special actions before or after invoking the original method. When uninstalled, the original method is returned to its rightful position in the method dictionary.

Pragmas

A pragma is an annotation that specifies data about a program, but is not involved in the execution of the program. Pragmas have no direct effect on the operation of the method they annotate. Pragmas have a number of uses, among them:

- Information for the compiler: pragmas can be used by the compiler to make a method call a primitive function. This function has to be defined by the virtual machine or by an external plugging.

- Runtime processing: Some pragmas are available to be examined at runtime.

Chapter summary

Reflection refers to the ability to query, examine and even modify the metaob- jects of the run-time system as ordinary objects.

- The Inspector uses instVarAt: and related methods to query and modify “private” instance variables of objects.

- Send Behavior»allInstances to query instances of a class.

- The messages class, isKindOf:, respondsTo: etc. are useful for gathering metrics or building development tools, but they should be avoided in regular applications: they violate the encapsulation of objects and make your code harder to understand and maintain.

- SystemNavigation is a utility class holding many useful queries for navi- gation and browsing the lass hierarhy. For example, use SystemNavigation default browseMethodsWithSourceString: 'pharo'. to find and browse all meth- ods with a given source string. (Slow, but thorough!)

- Every Smalltalk class points to an instance of MethodDictionary which maps selectors to instances of CompiledMethod. A compiled method knows its class, closing the loop.

- MethodReference is a leightweight proxy for a compiled method, pro- viding additional convenience methods, and used by many Smalltalk tools.

- BrowserEnvironment, part of the Refactoring Browser infrastructure, offers a more refined interface than SystemNavigation for querying the system, since the result of a query can be used as a the scope of a new query. Both GUI and programmatic interfaces are available.

- thisContext is a pseudo-variable that reifies the run-time stack of the virtual machine. It is mainly used by the debugger to dynamically construct an interactive view of the stack. It is also especially useful for dynamically determining the sender of a message.

- Intelligent breakpoints can be set using haltIf:, taking a method selector as its argument. haltIf: halts only if the named method occurs as a sender in the run-time stack.

- A common way to intercept messages sent to a given target is to use a “minimal object” as a proxy for that target. The proxy implements as few methods as possible, and traps all message sends by implementing doesNotunderstand:. It can then perform some additional action and then forward the message to the original target.

- Send become: to swap the references of two objects, such as a proxy and its target.

- Beware, some messages, like class and yourself are never really sent, but are interpreted by the VM. Others, like +, − and ifTrue: may be directly interpreted or inlined by the VM depending on the receiver.

- Another typical use for overriding doesNotUnderstand: is to lazily load or compile missing methods.

- doesNotUnderstand: cannot trap self-sends.

- A more rigorous way to intercept messages is to use an object as a method wrapper. Such an object is installed in a method dictionary in place of a compiled method. It should implement run:with:in: which is sent by the VM when it detects an ordinary object instead of a compiled method in the method dictionary. This technique is used by the SUnit Test Runner to collect coverage data.