Basic Classes

Most of the magic of Smalltalk is not in the language but in the class libraries. To program effectively with Smalltalk, you need to learn how the class libraries support the language and environment. The class libraries are entirely written in Smalltalk and can easily be extended since a package may add new functionality to a class even if it does not define this class.

Our goal here is not to present in tedious detail the whole of the Pharo class library, but rather to point out the key classes and methods that you will need to use or override to program effectively. In this chapter we cover the basic classes that you will need for nearly every application: Object, Number and its subclasses, Character, String, Symbol and Boolean.

Object

The class comment for the Object states:

Object is the root class for almost all of the other classes in the class hierarchy. The exceptions are ProtoObject (the superclass of Object) and its subclasses. Class Object provides default behaviour common to all normal objects, such as access, copying, comparison, error handling, message sending, and reflection. Also utility messages that all objects should respond to are defined here. Object has no instance variables, nor should any be added. This is due to several classes of objects that inherit from Object that have special implementations (SmallInteger and UndefinedObject for example) or the VM knows about and depends on the structure and layout of certain standard classes.

Class membership

Several methods allow you to query the class of an object.

class. You can ask any object about its class using the message class.

1 class ---> SmallInteger

Conversely, you can ask if an object is an instance of a specific class:

1 isMemberOf: SmallInteger

---> true "must be precisely this class"

1 isMemberOf: Integer

---> false

1 isMemberOf: Number

---> false

1 isMemberOf: Object

---> false

isKindOf: Object»isKindOf: answers whether the receiver’s class is either the same as, or a subclass of the argument class.

1 isKindOf: SmallInteger

---> true

1 isKindOf: Integer

---> true

1 isKindOf: Number

---> true

1 isKindOf: Object

---> true

1 isKindOf: String

---> false

1/3 isKindOf: Number

---> true

1/3 isKindOf: Integer

---> false

1/3 which is a Fraction is a kind of Number, since the class Number is a superclass of the class Fraction, but 1/3 is not a Integer.

respondsTo: Object»respondsTo: answers whether the receiver understands the message selector given as an argument.

1 respondsTo: #,

---> false

Normally it is a bad idea to query an object for its class, or to ask it which messages it understands. Instead of making decisions based on the class of object, you should simply send a message to the object and let it decide (i.e., on the basis of its class) how it should behave.

Copying

Copying objects introduces some subtle issues. Since instance variables are accessed by reference, a shallow copy of an object would share its references to instance variables with the original object:

a1 := { { 'harry' } }.

a1 ---> #(#('harry'))

a2 := a1 shallowCopy.

a2 ---> #(#('harry'))

(a1 at: 1) at: 1 put: 'sally'.

a1 ---> #(#('sally'))

a2 ---> #(#('sally')) "the subarray is shared"

Object >> copyTwoLevel does the obvious thing when a simple shallow copy does not suffice:

a1 := { { 'harry' } } .

a2 := a1 copyTwoLevel.

(a1 at: 1) at: 1 put: 'sally'.

a1 ---> #(#('sally'))

a2 ---> #(#('harry')) "fully independent state"

Object >> deepCopy makes an arbitrarily deep copy of an object.

a1 := { { { 'harry' } } } .

a2 := a1 deepCopy.

(a1 at: 1) at: 1 put: 'sally'.

a1 ---> #(#('sally'))

a2 ---> #(#(#('harry')))

The problem with deepCopy is that it will not terminate when applied to a mutually recursive structure:

Debugging

The most important method here is halt. In order to set a breakpoint in a method, simply insert the message send self halt at some point in the body of the method. When this message is sent, execution will be interrupted and a debugger will open to this point in your program. (See Chapter 6 for more details about the debugger.)

The next most important message is assert:, which takes a block as its argument. If the block returns true, execution continues. Otherwise an AssertionFailure exception will be raised. If this exception is not otherwise caught, the debugger will open to this point in the execution. assert: is especially useful to support design by contract. The most typical usage is to check non-trivial pre-conditions to public methods of objects.

Do not confuse Object >> assert: with TestCase >> assert:, which occurs in the SUnit testing framework (see Chapter 7). While the former expects a block as its argument1, the latter expects a Boolean. Although both are useful for debugging, they each serve a very different intent.

Error handling

This protocol contains several methods useful for signaling run-time errors.

Sending self deprecated: anExplanationString signals that the current method should no longer be used, if deprecation has been turned on in the debug protocol of the preference browser. The String argument should offer an alternative.

1 doIfNotNil: [ :arg | arg printString, ' is not nil' ]

---> SmallInteger(Object) >> doIfNotNil: has been deprecated. use ifNotNilDo:

doesNotUnderstand: is sent whenever message lookup fails. The default implementation, i.e., Object >> doesNotUnderstand: will trigger the debugger at this point. It may be useful to override doesNotUnderstand: to provide some other behaviour.

Object >> error and Object >> error: are generic methods that can be used to raise exceptions. (Generally it is better to raise your own custom exceptions, so you can distinguish errors arising from your code from those coming from kernel classes.)

Abstract methods in Smalltalk are implemented by convention with the body self subclassResponsibility. Should an abstract class be instantiated by accident, then calls to abstract methods will result in Object >> subclassResponsibility being evaluated.

Testing

The testing methods have nothing to do with SUnit testing! A testing method is one that lets you ask a question about the state of the receiver and returns a Boolean.

Numerous testing methods are provided by Object. We have already seen isComplex. Others include isArray, isBoolean, isBlock, isCollection and so on. Generally such methods are to be avoided since querying an object for its class is a form of violation of encapsulation. Instead of testing an object for its class, one should simply send a request and let the object decide how to handle it.

Nevertheless some of these testing methods are undeniably useful. The most useful are probably ProtoObject >> isNil and Object»notNil (though the Null Object2 design pattern can obviate the need for even these methods).

Initialize release

A final key method that occurs not in Object but in ProtoObject is initialize.

initialize as an empty hook method

ProtoObject >>

initialize

"Subclasses should redefine this method to perform initializations on instance creation"

The reason this is important is that in Pharo, the default new method defined for every class in the system will send initialize to newly created instances.

new as a class-side template method

Behavior >>

new

"Answer a new initialized instance of the receiver (which is a class) with no indexable variables. Fail if the class is indexable."

^ self basicNew initialize

This means that simply by overriding the initialize hook method, new instances of your class will automatically be initialized. The initialize method should normally perform a super initialize to establish the class invariant for any inherited instance variables. (Note that this is not the standard behaviour of other Smalltalks.)

Numbers

Remarkably, numbers in Smalltalk are not primitive data values but true objects. Of course numbers are implemented efficiently in the virtual machine, but the Number hierarchy is as perfectly accessible and extensible as any other portion of the Smalltalk class hierarchy.

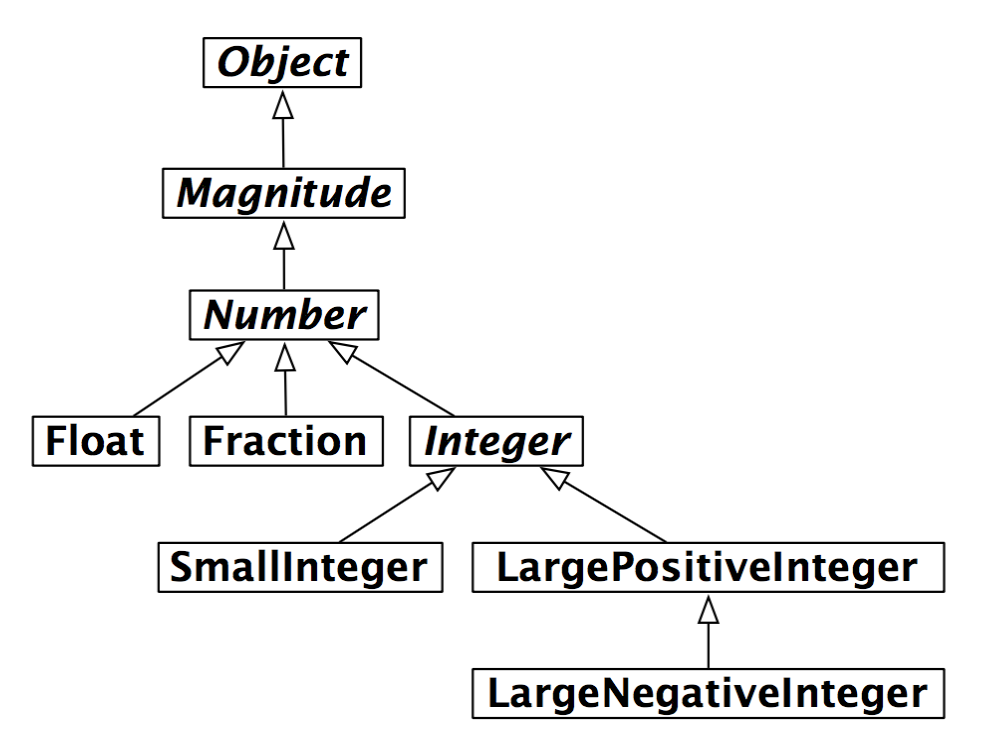

The Number Hierarchy

The Number Hierarchy

Numbers are found in the Kernel-Numbers category. The abstract root of this hierarchy is Magnitude, which represents all kinds of classes supporting comparision operators. Number adds various arithmetic and other operators as mostly abstract methods. Float and Fraction represent, respectively, floating point numbers and fractional values. Integer is also abstract, thus distinguishing between subclasses SmallInteger, LargePositiveInteger and LargeNegativeInteger. For the most part users do not need to be aware of the difference between the three Integer classes, as values are automatically converted as needed.

Magnitude

Magnitude is the parent not only of the Number classes, but also of other classes supporting comparison operations, such as Character, Duration and Timespan. (Complex numbers are not comparable, and so do not inherit from Number.)

Number

Similarly, Number defines +, −, * and / to be abstract, but all other arithmetic operators are generically defined.

All Number objects support various converting operators, such as asFloat and asInteger. There are also numerous shortcut constructor methods, such as i, which converts a Number to an instance of Complex with a zero real component, and others which generate Durations, such as hour, day and week.

Numbers directly support common math functions such as sin, log, raiseTo:, squared, sqrt and so on.

Number»printOn: is implemented in terms of the abstract method Number» printOn:base:. (The default base is 10.)

Testing methods include even, odd, positive and negative. Unsurprisingly Number overrides isNumber. More interesting, isInfinite is defined to return false.

Truncation methods include floor, ceiling, integerPart, fractionPart and so on.

|---+---+---+---| | 1 + 2.5 | ---> | 3.5 | "Addition of two numbers" | | 3.4 * 5 | ---> | 17.0 | "Multiplication of two numbers" | | 8 / 2 | ---> | 4 | "Division of two numbers" | | 10 − 8.3 | ---> | 1.7 | "Subtraction of two numbers" | 12 = 11 | ---> | false | "Equality between two numbers" | | 12 >= 11 | ---> | true | "Test if two numbers are different" | 12 > 9 | ---> | true | "Greater than" | | 12 >= 10 | ---> | true | "Greater or equal than" | | 12 < 10 | ---> | false | "Smaller than" | | 100@10 | ---> | 100@10 | "Point creation" |

Float

Float implements the abstract Number methods for floating point numbers. More interestingly, Float class (i.e., the class-side of Float) provides methods to return the following constants: e, infinity, nan and pi.

|---+---+---| | Float pi | ---> | 3.141592653589793 | | Float infinity | ---> | Infinity | | Float infinity isInfinite | ---> | true |

Fraction

Fractions are represented by instance variables for the numerator and denominator, which should be Integers. Fractions are normally created by Integer division (rather than using the constructor method Fraction»numerator:denominator:):

|---+---+---| | 6/8 | ---> | (3/4) | | (6/8) class | ---> | Fraction |

Multiplying a Fraction by an Integer or another Fraction may yield an Integer:

|---+---+---| | 6/8*4 | ---> | 3 |

Integer

Integer is the abstract parent of three concrete integer implementations. In addition to providing concrete implementations of many abstract Number methods, it also adds a few methods specific to integers, such as factorial, atRandom, isPrime, gcd: and many others.

SmallInteger is special in that its instances are represented compactly — instead of being stored as a reference, a SmallInteger is represented directly using the bits that would otherwise be used to hold a reference. The first bit of an object reference indicates whether the object is a SmallInteger or not.

Characters

Character is defined in the Collections-Strings category as a subclass of Magnitude. Printable characters are represented in Pharo as $\<char>. For example:

|---+---+---| | $a < $b | ---> | true |

Non-printing characters can be generated by various class methods. Character class»value: takes the Unicode (or ASCII) integer value as argument and returns the corresponding character. The protocol accessing untypeable characters contains a number of convenience constructor methods such as backspace, cr, escape, euro, space, tab, and so on.

Character space = (Character value: Character space asciiValue) ≠æ true

The printOn: method is clever enough to know which of the three ways to generate characters offers the most appropriate representation:

|---+---+---| | Character value: 1 | ---> | Character home | | Character value: 2 | ---> | Character value: 2 | | Character value: 32 | ---> | Character space | | Character value: 97 | ---> | $a |

Various convenient testing methods are built in: isAlphaNumeric, isCharacter, isDigit, isLowercase, isVowel, and so on.

Strings

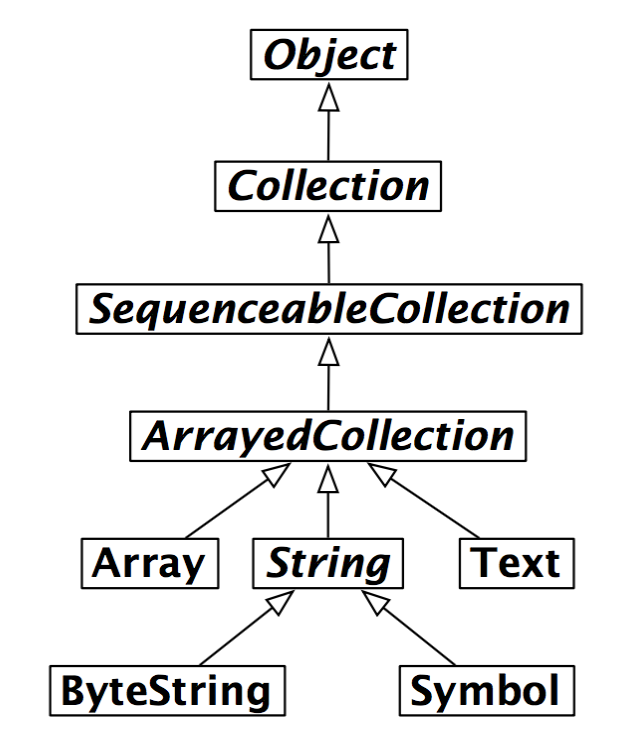

The String class is also defined in the category Collections-Strings. A String is an indexed Collection that holds only Characters.

The String Hierarchy

In fact, String is abstract and Pharo Strings are actually instances of the concrete class ByteString.

|---+---+---| | Character value: 97 | ---> | $a | | 'hello world' class | ---> | ByteString |  The other important subclass of String is Symbol. The key difference is that there is only ever a single instance of Symbol with a given value. (This is sometimes called “the unique instance property”). In contrast, two separately constructed Strings that happen to contain the same sequence of characters will often be different objects.

| 'hel','lo' == 'hello' | ---> | false | | ('hel','lo') asSymbol == #hello | ---> | true |

Another important difference is that a String is mutable, whereas a Symbol is immutable.

| 'hello' at: 2 put: $u; yourself | ---> | 'hullo' | | #hello at: 2 put: $u | ---> | error |

Booleans

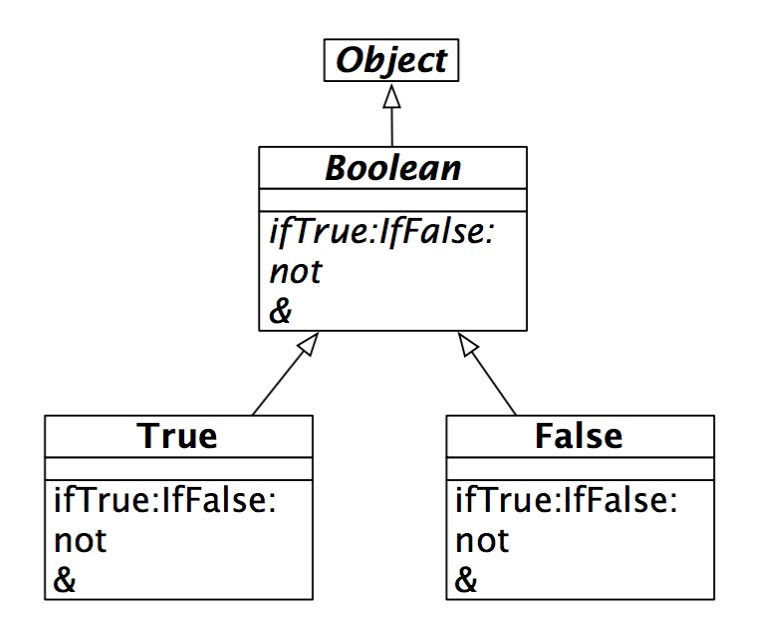

The class Boolean offers a fascinating insight into how much of the Smalltalk language has been pushed into the class library. Boolean is the abstract super- class of the Singleton classes True and False.

Most of the behaviour of Booleans can be understood by considering the method ifTrue:ifFalse:, which takes two Blocks as arguments.

The Boolean Hierarchy

The method is abstract in Boolean. The implementations in its concrete subclasses are both trivial:

Implementations of ifTrue:ifFalse:

True >>

ifTrue: trueAlternativeBlock ifFalse: falseAlternativeBlock

^ trueAlternativeBlock value

False >> ifTrue: trueAlternativeBlock ifFalse: falseAlternativeBlock ^ falseAlternativeBlock value

Chapter summary

- If you override = then you should override hash as well.

- Override postCopy to correctly implement copying for your objects.

- Send self halt to set a breakpoint.

- Return self subclassResponsibility to make a method abstract.

- To give an object a String representation you should override printOn:.

- Override the hook method initialize to properly initialize instances.

- Number methods automatically convert between Floats, Fractions and Integers.

- Fractions truly represent rational numbers rather than floats.

- Characters are unique instances.

- Strings are mutable; Symbols are not. Take care not to mutate string literals, however!

- Symbols are unique; Strings are not.

- Strings and Symbols are Collections and therefore support the usual Collection methods.