The Smalltalk object model

The rules of the model

- Rule 1. Everything is an object.

- Rule 2. Every object is an instance of a class.

- Rule 3. Every class has a superclass.

- Rule 4. Everything happens by sending messages.

- Rule 5. Method lookup follows the inheritance chain.

Everything is an Object

Classes are objects too.

Deep in the implementation of Smalltalk, there are three different kinds of objects.

There are

(1) ordinary objects with instance variables that are passed by references,

there are

(2) small integers that are passed by value,

and there are

(3) indexable objects like arrays that hold a contiguous portion of memory. The beauty of Smalltalk is that you normally don’t need to care about the differences between these three kinds of object.

Every object is an instance of a class

|---+---+---| | 1 class | ---> | SmallInteger | | 20 factorial class | ---> | LargePositiveInteger | | 'hello' class | ---> | ByteString | | #(1 2 3) class | ---> | Array | | (4@5) class | ---> | Point | | Object new class | ---> | Object| | | |

A class defines the structure of its instances via instance variables, and the behavior of its instances via methods. Each method has a name, called its selector, which is unique within the class.

Since classes are objects, and every object is an instance of a class, it follows that classes must also be instances of classes. A class whose instances are classes is called a metaclass. Whenever you create a class, the system automatically creates a metaclass for you. The metaclass defines the structure and behavior of the class that is its instance. 99% of the time you will not need to think about metaclasses, and may happily ignore them.

Instance variables

Methods

A class does not have access to the instance variables of its own instances.

An instance of a class does not have access to the class instance variables of its class.

Every class has a superclass

Abstract methods and abstract classes

Smalltalk has no dedicated syntax to specify that a method or a class is abstract. By convention, the body of an abstract method consists of the expression self subclassResponsibility. This is known as a “marker method”, and indicates that subclasses have the responsibility to define a concrete version of the method. self subclassResponsibility methods should always be overridden, and thus should never be executed. If you forget to override one, and it is executed, an exception will be raised.

Traits

A trait is a collection of methods that can be included in the behaviour of a class without the need for inheritance. This makes it easy for classes to have a unique superclass, yet still share useful methods with otherwise unrelated classes. To define a new trait, simply replace the subclass creation template by a message to the class Trait.

Defining a new trait

1

2

3

Trait named: #TAuthor

uses: { }

category: 'PBE−LightsOut'

Here we define the trait TAuthor in the category PBE-LightsOut. This trait does not use any other existing traits. In general we can specify a trait composition expression of other traits to use as part of the uses: keyword argument. Here we simply provide an empty array.

Traits may contain methods, but no instance variables. Suppose we would like to be able to add an author method to various classes, independent of where they occur in the hierarchy. We might do this as follows:

An author method

1

2

3

4

TAuthor >> author:

"Return author initials"

"oscar nierstrasz"

^ 'on'

Using a trait

1

2

3

4

5

BorderedMorph subclass: #LOGame

uses: TAuthor

instanceVariableNames: 'cells'

classVariableNames: '' poolDictionaries: ''

category: 'PBE−LightsOut'

If we now instantiate LOGame, it will respond to the author message as expected.

1

Game new author -> 'on'

Everything happens by sending messages

This rule captures the essence of programming in Smalltalk. In procedural programming, the choice of which piece of code to execute when a procedure is called is made by the caller. The caller chooses the procedure or function to execute statically, by name.

In object-oriented programming, we do not “call methods”: we “send messages.” The choice of terminology is significant. Each object has its own responsibilities. We do not tell an object what to do by applying some procedure to it. Instead, we politely ask an object to do something for us by sending it a message. The message is not a piece of code: it is nothing but a name and a list of arguments. The receiver then decides how to respond by selecting its own method for doing what was asked. Since different objects may have different methods for responding to the same message, the method must be chosen dynamically, when the message is received.

1

2

3 + 4 -> 7 "send message + with argument 4 to integer 3"

(1@2) + 4 -> 5@6 "send message + with argument 4 to point (1@2)"

As a consequence, we can send the same message to different objects, each of which may have its own method for responding to the message. We do not tell the SmallInteger 3 or the Point 1@2 how to respond to the message + 4. Each has its own method for +, and responds to + 4 accordingly.

One of the consequences of Smalltalk’s model of message sending is that it encourages a style in which objects tend to have very small methods and delegate tasks to other objects, rather than implementing huge, procedural methods that assume too much responsibility. Joseph Pelrine expresses this principle succinctly as follows:

Don’t do anything that you can push off onto someone else.

Many object-oriented languages provide both static and dynamic opera- tions for objects; in Smalltalk there are only dynamic message sends. Instead of providing static class operations, for instance, classes are objects and we simply send messages to classes.

Nearly everything in Smalltalk happens by sending messages. At some point action must take place:

- Variable declarations are not message sends. In fact, variable declarations are not even executable. Declaring a variable just causes space to be allocated for an object reference.

- Assignments are not message sends. An assignment to a variable causes that variable name to be freshly bound in the scope of its definition.

- Returns are not message sends. A return simply causes the computed result to be returned to the sender.

- Primitives are not message sends. They are implemented in the virtual machine.

Other than these few exceptions, pretty much everything else does truly happen by sending messages. In particular, since there are no “public fields” in Smalltalk, the only way to update an instance variable of another object is to send it a message asking that it update its own field. Of course, providing setter and getter methods for all the instance variables of an object is not good object-oriented style. Joseph Pelrine also states this very nicely:

Don’t let anyone else play with your data.

Method lookup follows the inheritance chain

- What happens when a method does not explicitly return a value?

- What happens when a class reimplements a superclass method?

- What is the difference between self and super sends?

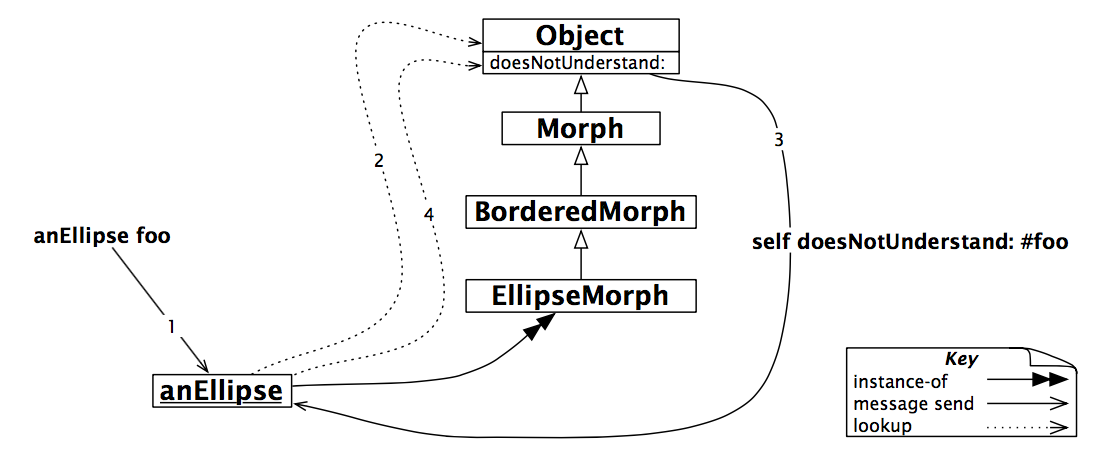

- What happens when no method is found?

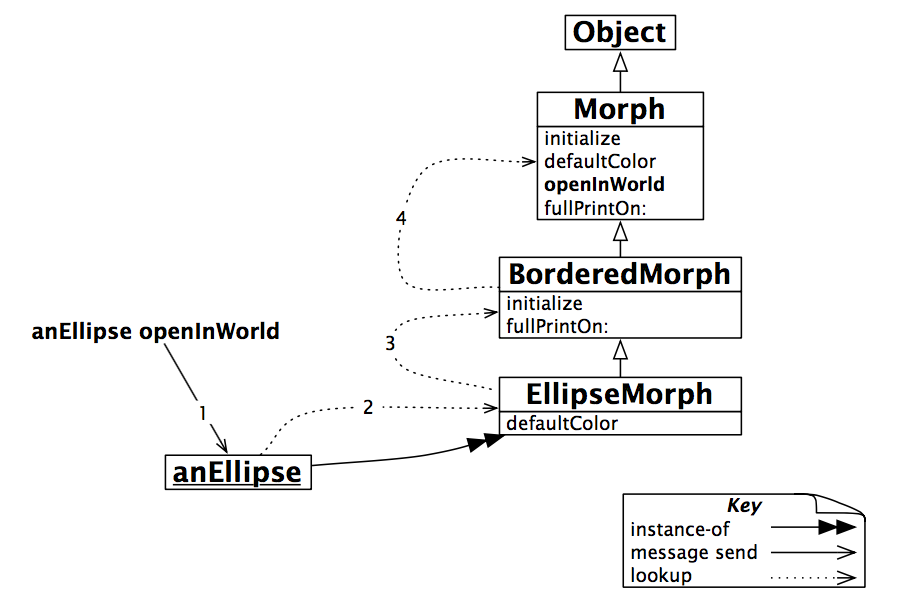

Method lookup follows the inheritance hierarchy.

Return a value only when you intend for the sender to use the value.

Overriding and extension

Super initialize

1

2

3

4

BorderedMorph»initialize

"initialize the state of the receiver"

super initialize.

self borderInitialize

An initialize method should always start by sending super

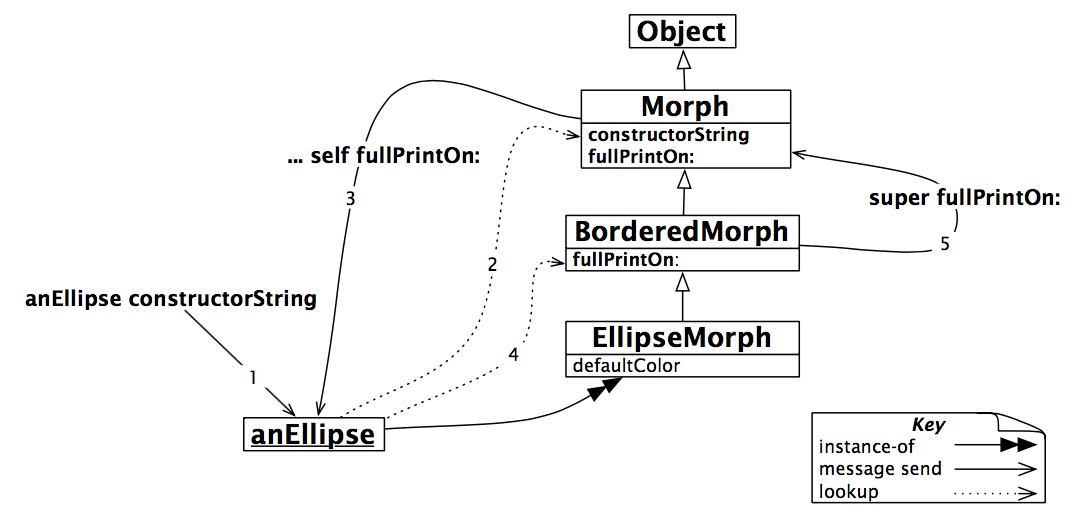

Self sends and super sends

We need super sends to compose inherited behaviour that would otherwise be overridden. The usual way to compose methods, whether inherited or not, however, is by means of self sends. How do self sends differ from super sends? Like self, super represents the receiver of the message. The only thing that changes is the method lookup. Instead of lookup starting in the class of the receiver, it starts in the superclass of the class of the method where the super send occurs.

Self sends and super sends

self and super sends

A self send triggers a dynamic method lookup starting in the class of the receiver.

A super send triggers a static method lookup starting in the superclass of the class of the method performing the super send.

Message not understood

Message foo is not understood

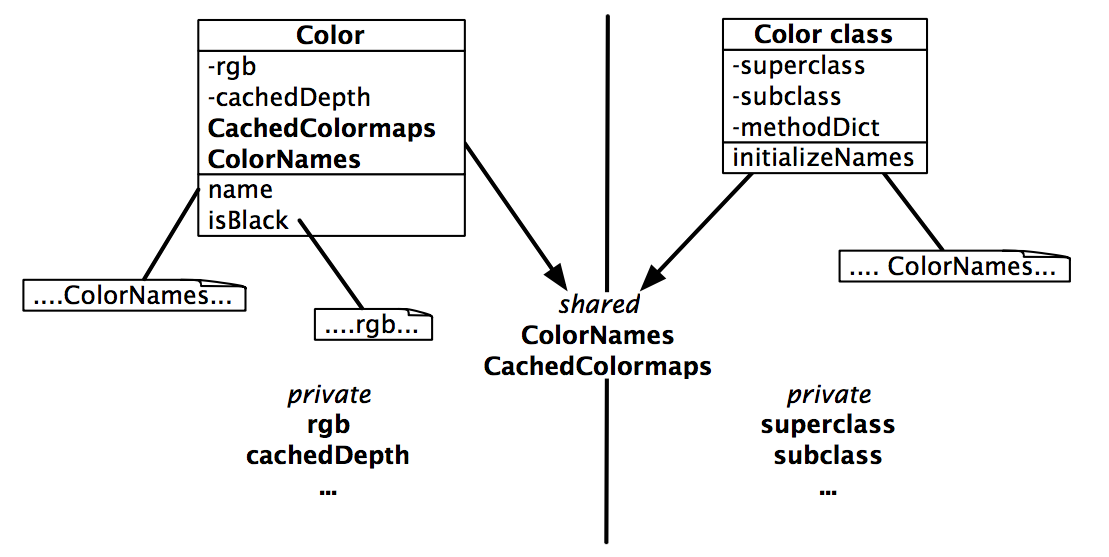

Shared variables

Smalltalk provides three kinds of shared variables:

- globally shared variables;

- variables shared between instances and classes (class variables), and

- variables shared amongst a group of classes (pool variables). The names of all of these shared variables start with a capital letter, to warn us that they are indeed shared between multiple objects.

Global variables

In Pharo, all global variables are stored in a namespace called Smalltalk, which is implemented as an instance of the class SystemDictionary. Global variables are accessible everywhere. Every class is named by a global variable; in addition, a few globals are used to name special or commonly useful objects. The variable Transcript names an instance of TranscriptStream, a stream that writes to a scrolling window. The following code displays some information and then goes to the next line in the Transcript.

- Smalltalk is theinstance of SystemDictionary that defines all of the globals— including Smalltalk itself. The keys to this dictionary are the symbols that name the global objects in Smalltalk code.

- Sensor is an instance of EventSensor, and represents input to Pharo. For example, Sensor keyboard answers the next character input on the key- board, and Sensor leftShiftDown answers true if the left shift key is being held down, while Sensor mousePoint answers a Point indicating the cur- rent mouse location.

- World is an instance of PasteUpMorph that represents the screen. World bounds answers a rectangle that defines the whole screen space; all Morphs on the screen are submorphs of World.

- ActiveHand is the current instance of HandMorph, the graphical representa- tion of the cursor. ActiveHand’s submorphs hold anything being dragged by the mouse.

- Undeclared is another dictionary — it contains all the undeclared vari- ables. If you write a method that references an undeclared variable, the browser will normally prompt you to declare it, for example, as a global or as an instance variable of the class. However, if you later delete the declaration, the code will then reference an undeclared variable. Inspecting Undeclared can sometimes help explain strange behaviour!

- SystemOrganization is an instance of SystemOrganizer: it records the organi- zation of classes into packages. More precisely, it categorizes the names of classes.

Class variables

Instance and class methods accessing different variables.

Pool variables

Once again, we recommend that you avoid the use of pool variables and pool dictionaries.

Chapter summary

The object model of Pharo is both simple and uniform. Everything is an object, and pretty much everything happens by sending messages.

- Everything is an object. Primitive entities like integers are objects, but also classes are first-class objects.

- Every object is an instance of a class. Classes define the structure of their instances via private instance variables and the behaviour of their instances via public methods. Each class is the unique instance of its metaclass. Class variables are private variables shared by the class and all the instances of the class. Classes cannot directly access instance vari- ables of their instances, and instances cannot access instance variables of their class. Accessors must be defined if this is needed.

- Every class has a superclass. The root of the single inheritance hier- archy is ProtoObject. Classes you define, however, should normally inherit from Object or its subclasses. There is no syntax for defining abstract classes. An abstract class is simply a class with an abstract method — one whose implementation consists of the expression self subclassResponsibility. Although Pharo supports only single inheritance, it is easy to share implementations of methods by packaging them as traits. * Everything happens by sending messages. We do not “call methods”, we “send messages”. The receiver then chooses its own method for responding to the message.

- Method lookup follows the inheritance chain; self sends are dynamic and start the method lookup again in the class of the receiver, whereas super sends are static, and start in the superclass of class in which the super send is written.

- There are three kinds of shared variables. Global variables are accessible everywhere in the system. Class variables are shared between a class, its subclasses and its instances. Pool variables are shared between a selected set of classes. You should avoid shared variables as much as possible.